By Ramathan Ggoobi;

On April 28, I delivered the inaugural Tumusiime-Mutebile Memorial Lecture at Makerere University. During the lecture, I commented about the unfinished business the former Bank of Uganda Governor left behind and would want us to address to propel Uganda to the level he and all of us want it to get to.

One of the key examples of the unfinished business is the need to upscale our level of industrialization, to add value to the raw materials we produce (especially agricultural produce and minerals) and to create more productive jobs for the millions of young Ugandans that are currently unemployed or underemployed.

When I made a comment that agriculture does not transform a country, many people understandably felt uncomfortable with that assertion. Why? First, we are a predominantly agrarian economy, with 72 of every 100 Ugandans working in agriculture. In addition, many of the remaining 28% Ugandans working outside agriculture own a farm (in fact a garden) either as a hobby or for side income.

Secondly, most people who commented listened to a short video cutout of the long speech that contained context and more explanation. In addition, given the current government policy to invest more in agriculture in order to pull the 3.5 million households stuck in the subsistence economy and integrate them in the monetary economy, it would sound contradictory for me to make such an assertion.

I, therefore, wrote this to explain in much more detail what I meant, and most importantly, to elaborate what the government is doing to make the economy work for all Ugandans, particularly those locked up in subsistence agriculture as well as the unemployed youth.

As late comers to development, it is logical for poor countries such as Uganda to ask ourselves how the developed countries transformed themselves from stagnation to growth, and from low-income to high-income status, and most importantly, how they overcame poverty.

How did the Americans, the Canadians, the Europeans and more recently the East Asians make themselves achieve the high physical quality of life and affluence they enjoy today?

The greater majorities of the populations in rich countries are well fed and well dressed, have easy access to a variety of goods and services that we struggle to access, have good housing, live in a healthy environment, and when they fall sick they receive proper medical care. Have they been this affluent throughout history?

These are questions worth our time. They are questions top researchers in development economics have taken trouble to find answers for. Below are some of well-documented facts beyond personal opinion.

First, all the countries we admire, because of their high levels of social, economic and political wellbeing were once poor and predominantly agrarian. To achieve the economic status they enjoy today, these countries underwent deliberate economic transformation.

What is economic transformation?

By economic transformation, economists refer to a change in the structure of the economy from a subsistence to industrialised state. Economic transformation entails four interrelated processes. These are:

- a decline in the share of agriculture in the country’s output (GDP) and employment. This is an unambiguous trend over the course of economic development.

- a rise of a modern industrial and service economy (in both GDP and employment)

- a rapid process of urbanisation (with most of the people moving from rural areas to live in cities and/or urban centres).

- a demographic transition from high to low rates of births and deaths.

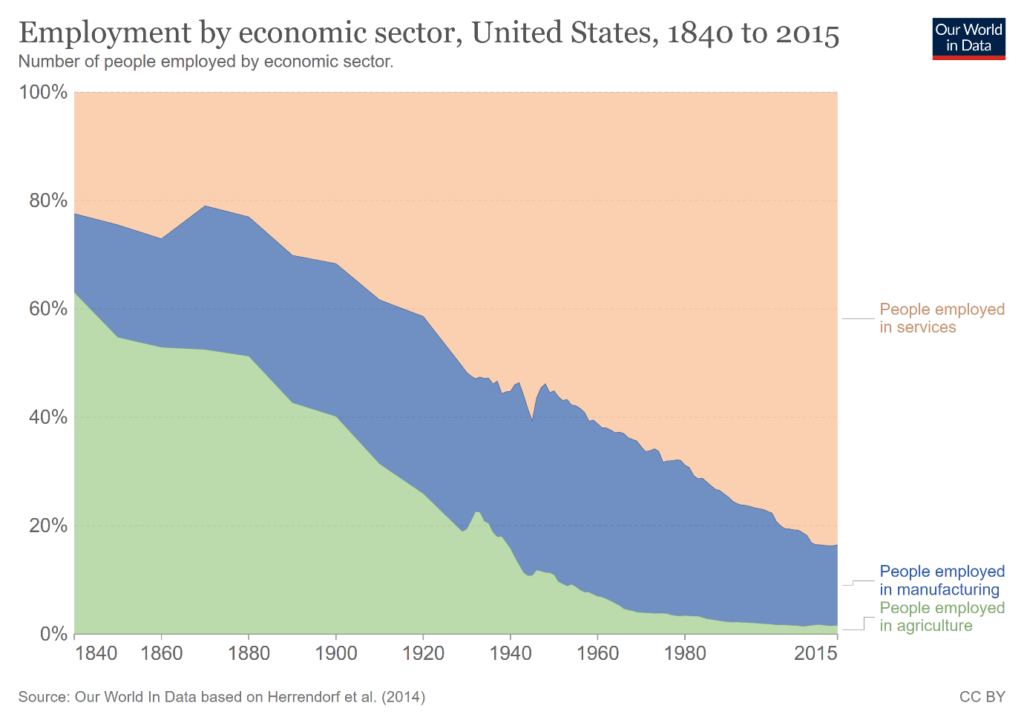

The second key fact is that all countries that have transformed their economies did so by industrialising. In all today’s rich countries, the share of workers employed in agriculture continually went down while the share of those employed in the services and industrial sectors went up. But for the manufacturing sector, it first increased (peaking at over 30% of GDP) and then decreased in relative importance as today’s rich economies transformed.

Why does the share of agriculture in GDP and employment have to decline for a country to transform? Agriculture is the sector with least ability to take advantage of global incomes as they keep rising. Food and other agricultural products have low income elasticity of demand. That is, as people’s incomes rise, the fraction of the incomes spent on food or agriculture products declines while that spent on manufactured items and modern services (such as banking, telecommunication, insurance, transport, hospitality and leisure etc.) increases.

For example, a person will use one tea bag whether they are low income earners or billionaires. On the other hand, as people’s incomes rise, they tend to buy more manufactures such as garments, shoes, gadgets, and services like banking, insurance, hotels, etc.

In all rich economies most of their populations are employed in the services and industrial sectors because these are the sectors that tend to take full advantage of global, regional and domestic incomes.

This attests to the well-documented fact that in comparison to the other sectors (i.e. in relative terms), agriculture tends to be the least productive sector in an economy. Historical evidence tells us a story that structural transformation is not one of a stagnant agricultural sector overtaken by dynamic manufacturing and service sectors. Instead, what matters are the differences in productivity growth between sectors.

Why we need to reduce people employed by agriculture

Researchers have indicated that at early stages of development, technological improvements in manufacturing are the greatest contributors to ‘pulling’ workers out of agriculture.

At later stages, the decline in the share of consumption devoted to food and other agricultural goods, combined with continued improvements in agricultural technology, become the predominant force in releasing workers from agriculture.

There is often confusion about countries with well performing agricultural sectors such as the Netherlands. Some people erroneously think it’s agriculture that transformed their economies or that agriculture is their main sector today. Neither of such beliefs is correct. Although the Netherlands has traditionally had a vibrant agricultural sector, her development was mainly driven by the industrial and service sectors.

Anyone interested in economic history knows that the so-called Dutch Golden Age (starting in the 17th Century) was characterised not by agriculture but by merchant marine, totaling 568,000 tons of shipping – about half the European total.

The Dutch economy then was driven by sectors such as trade, labour-intensive industries such as textiles, salt refining, construction, fishing net manufacturing, food processing, and specialised shipbuilding, as well as the financial sector. Amsterdam became the leading commercial and financial centre of the world way back in the 17th Century.

Today’s enviable Dutch agricultural sector has historically also been very efficient and productive, specialising in less labour-intensive livestock and very labour-intensive industrial crop production, particularly horticulture.

But today agriculture contributes only 1.6% of the Dutch economy’s GDP and employs only 2% of the population. A lion’s share of the Dutch GDP (70%) is produced by the services sector, followed by industry (28.4%) of which 10.6% is by manufacturing. Today, the Netherlands is a leading European supplier of chemical products and services and renewable energy.

Agriculture needs less people to ensure food security

Another misconception among some people is the thinking that by having more people in agriculture we shall ensure food security. Contrary to this commonsense, countries have made themselves more food secure by reducing the number of their citizens that are farming. Food secure nations invest more in farmer productivity such that fewer farmers produce more food to feed the rest of the population working in the modern and more productive sectors.

In rich and food secure countries, less than 2% of their populations are employed by agriculture – USA (1%), UK (1%), Germany (1%), Israel (1%), Sweden (2%), Norway (2%), Netherlands (2%), Denmark (2%), and Canada (2%) among others.

In comparison, food insecure countries are the ones where more than half of their population are farmers – Burundi (86%), Somalia (80%), Malawi (76%), Central African Republic (70%), Ethiopia (67%), Tanzania (65%), DRC (64%), Mali (64%), Rwanda (62%), South Sudan (60%), and Kenya (54%). In Uganda, 72% of the population is in agriculture.

The proportion of total population employed in agriculture globally is as follows: richest countries popularly known as high-income economies (3%), upper middle-income economies (21%), and low-income economies (60%). That shows clearly that poverty (low incomes) and food insecurity are associated with higher employment in agriculture.

The lesson from this is to strive to move beyond our traditional reliance on agriculture to achieve higher growth and protect Ugandans from food insecurity and poverty. But to do this, we need to start by investing in agricultural productivity by addressing the factors of production (capital, land, labour, entrepreneurship and markets). This is the vision of President Museveni and it’s well enshrined in his manifesto for 2021 – 2026.

The case for Parish Development Model

Our agenda now is to start a deliberate journey of facilitating “full monetisation of the economy through commercial agriculture, industrialisation, services, digital transformation and market access,” the theme of the 2022/23 National Budget.

Since we cannot do everything at the same time, we have started by addressing the factor of capital in a big way. Starting with next financial year, subsistence farmers will be supported with low-cost capital to purchase quality inputs to raise their output and productivity. In subsequent years, we shall scale up other factors including land rights, extension services, post-harvest management and value addition, and marketing.

Therefore, we are mindful that if we are to achieve rapid and pro-people industrial development, we must start with agro-industrialisation. In his book, How Asia Works, Joe Studwell summarises a simple and clear route to agro-industrialisation, showing that all countries that have succeeded in pursuing it used a three-part formula:

- They created conditions for small farmers to thrive by securing property rights of farmlands and investing in increasing farm yields per hectare;

- Used the proceeds from agricultural surpluses to build a manufacturing base that is tooled from the start to produce exports; and

- Nurtured both these sectors (smallholder farming and export-oriented manufacturing) with financial institutions closely controlled by the government.

In conclusion, the central aim of industrialisation is to create productive employment for the excess population stuck in agriculture (as subsistence farmers) and value addition to the raw materials both agricultural and minerals.

Economists widely accept that poverty reduction and economic development cannot be achieved without economic transformation and productivity change. The economy must transform from a heavy emphasis on traditional agriculture (especially in terms of employment) to a more industrial and service-oriented economy. The population working in agriculture must reduce since output/productivity tends to increase with fewer people working in the sector on larger pieces of land using modern technology.

All rich countries got rich by industrialising first before moving their populations into modern services. It’s also a fact that all industrialised nations used industrial policy i.e., government directly investing in industry and/or subsiding private investors to establish robust manufacturing firms. We are doing this and are going to scale up the effort.

The writer is the Permanent Secretary and Secretary to Treasury.